Urdu is the first language of over 70 million speakers and a second language to over 160 million people, mostly in Pakistan and India. Due to both design and engineering challenges, there were only a few typefaces available for the Urdu language in the preferred Nasta'liq writing style of the Arabic writing system. The scarcity of Nasta'liq typefaces was so dire that some newspapers and other printed materials were written by hand. Urdu speakers still sometimes write emails and messages in Romanized Urdu (the transliteration of Urdu in the Latin alphabet). Why are there so few Urdu fonts?

If there is such a large population of Urdu speakers, you might wonder why there are so few typefaces for this population. One reason is that technology companies have not seen Urdu-speaking communities as important markets and have not invested resources to develop Nasta’liq typefaces.

Let’s go back in history and review some features of the Urdu language, the Nasta'liq script, and technological problems to find some more reasons.

Writing the Urdu language

To a great extent, the Urdu language is similar to Hindi. Speakers of both languages can understand each other. Yet the writing systems used for each language are very different. Hindi is written from left to right in the Devanagari writing system, while Urdu is written from right to left in the Nasta'liq style of the Arabic writing system. When calligraphers used to write Nasta’liq by hand, they traditionally used a reed pen.

Reed pens used for Nasta’liq calligraphy, Photo credit: Borna Izadpanah

Nasta'liq was initially developed to represent the Persian language but has also been used to write other languages, including Ottoman Turkish, Kurdish, Pashto, Sindhi, Persian, and Uyghur. Today, most Arabic typefaces used for those languages in printed books, newspapers and digital platforms use a simplified form of the Naskh style. However, most Urdu books and newspapers are still printed with Nasta'liq type, which takes up more vertical space than simplified Naskh and has a more cursive style.

1. Nasta'liq

2. Naskh

Transliteration: Ab apne aap se bhi chup gai hai

An Urdu poetry verse (“Now she is hiding from herself too”) by the poet Zehra Nigah, set in the Gulzar Nasta’liq typeface (top) and in a simplified Naskh typeface Markazi (bottom).

Urdu cascades

Latin and many other writing systems can be written with unconnected letters and are more horizontally aligned on the baseline. In contrast, "most Arabic script writing styles are written in a cascading format in which characters are joined on multiple horizontal levels.” explained Borna Izadpanah, the designer of the Gulzar typeface.

Typesetting technologies have been primarily designed for non-joining and horizontally aligned scripts like Latin. The cascading nature makes Nasta'liq typeface design, production, and composition more software reliant than Naskh.

Designers have to find a solution for kerning the cascading forms and the precise positioning of diacritic dots for vowel marks to avoid clashes and overlaps.

|

From right to left. This animated GIF shows the composition of characters with kerning and also how dots and marks move around to avoid clashes and overlaps. Characters change shapes depending on the letters that come before and after. (Set in the Gulzar typeface.)

Translation: “How to type in Urdu on your computer”.

Transliteration: Apne computer pe Urdu mein kaise type karein

|

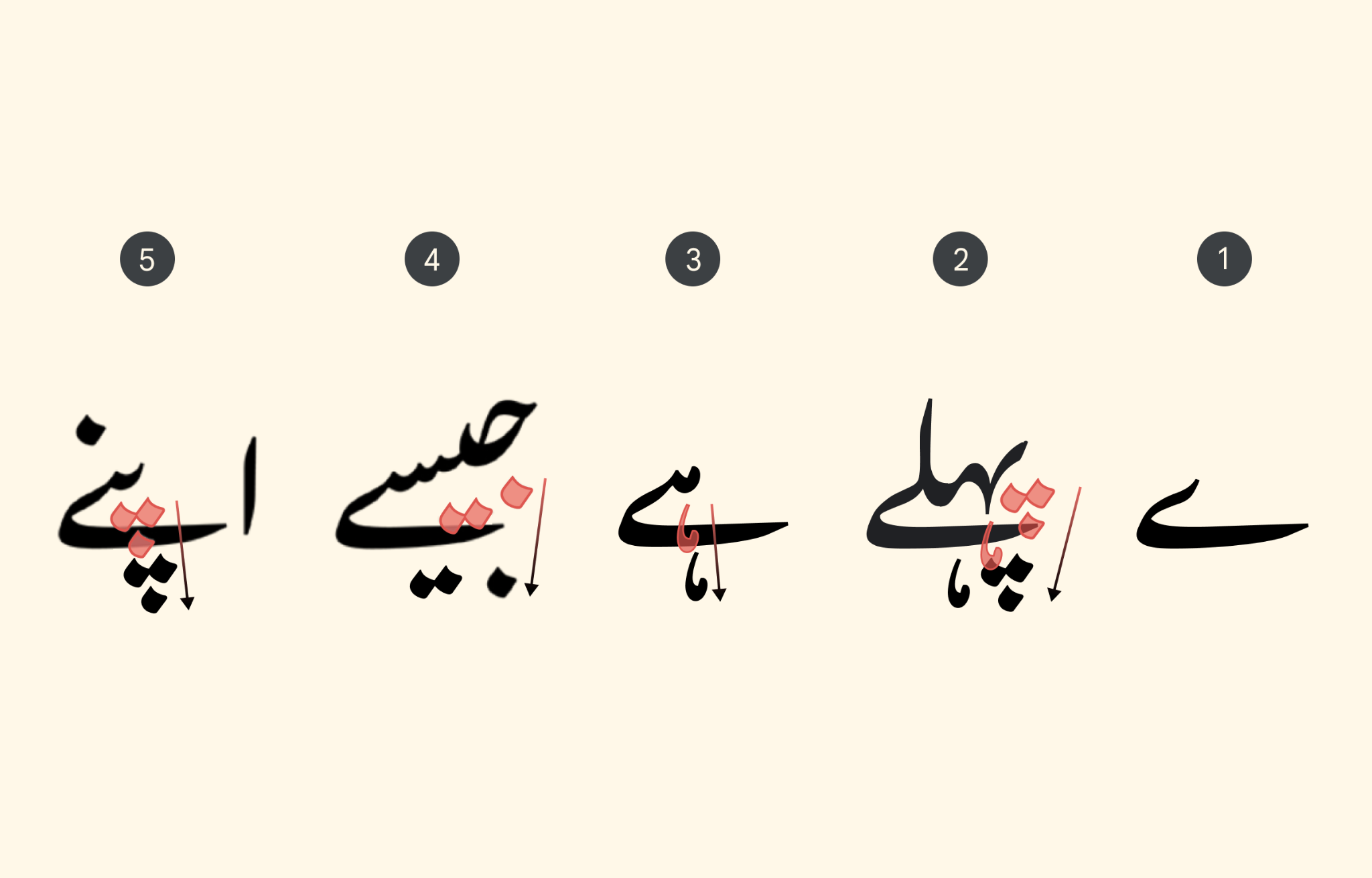

The bari-ye vowel

Designers have to pay special attention to the bari-ye vowel (ے, /eː/ /ɛː/) which frequently appears in Urdu. Even though Urdu is written from right to left, the bari-ye sweeps backwards (left to right) and underneath preceding letters, especially impacting dotted letters which precede it.

|

From right to left:

1. Unconnected form of bari-ye

2-5: Sequence of characters in words ending with bari-ye. The arrows show the downward shift of diacritical marks to avoid clashes and overlaps with the bari-ye.

(Set in the Gulzar typeface.)

|

Shapeshifting

In Nasta'liq, letters change their form based on their position in the word (initial, medial, final, and unconnected) and depending on the neighboring letters before and after.

From right to left: The letter پ (“P” sound) in initial position (circled and in red) taking different shapes based on the next letter. (Set in the Gulzar typeface.)

|

Latin has something similar to shapeshifting. In some Latin writing styles, letters change depending on their position and connection to the letters around them.

The angles of the connecting strokes of the lowercase “o” change depending on the following letter. Set in Style Script by Robert Leuschke.

One of the main differences between the Latin and Arabic writing systems is that Latin can be written in both connected cursive and unconnected forms, but the Arabic letters (apart from a few exceptions) must be written in a connected form. Additionally, most Arabic letters alter their shape depending on the preceding and following letters.

Technical difficulties

Urdu Nasta'liq is poorly supported on digital platforms because the writing system requires software-intensive support. Some text-rendering systems/software are not designed to accommodate it.

For a long time Urdu speakers have had to use existing simplified Naskh typefaces with distorted Urdu characters or find a way to hack operating systems to install their preferred Nasta'liq typefaces. However, this is changing.

Google Fonts has two Urdu Nasta'liq fonts, Noto Nasta'liq Urdu (a variable font) and Gulzar. To learn about how Gulzar was made and new tools to make typefaces for typographically complex scripts such as Nasta'liq, read Gulzar: Expanding the variety of Urdu Nasta’liq options.

To learn more about Urdu Nasta'liq:

The Death of the Urdu Script

How to bring a language to the future